How the telegraph put a stop to illicit drinking in Galway, and made Leopold Bloom think about astronomy instead of STIs. (6 minute read)

Early one summer morning in 1877, drinkers at Denis Kelly’s pub on Galway’s High Street were interrupted by an unwelcome visitor. Constable Joseph Merrifield of the RIC was not looking for an early-morning tipple but rather for illegal drinking and promptly accused Mr Kelly of opening his public house a whole eight minutes before the permitted opening hour of 7 o’clock. Possibly chancing his arm, Mr Kelly disputed the allegation, proffering his watch as proof that it was indeed after 7am and explaining that no law had been broken as he was following Dublin time. Constable Merrifield presented his own watch, which was set according to the town clock before charging Kelly with a breach of the licencing laws.

In the resultant case at Galway Magistrates Court, Mr Kelly contested the charge. A witness for the defence testified that his watch agreed with the publican’s, telling the court “that very morning he telegraphed for time, and was with Dublin”. The magistrates dismissed the case against Kelly. The police, no doubt exasperated, insisted on knowing from the magistrates what time they should use to determine similar breaches in the future — but to this question they received no definitive answer1.

The charge brought by Constable Merrifield’s against Mr Kelly in 1877 was not unreasonable. For as long as humans had measured time, they had done so based on the time the sun rose and set in the locality. The sun rises and sets about eleven minutes later in Galway than in Dublin and thus its local time was eleven minutes behind Dublin time. This system was perfectly adequate for a world where watches were uncommon, accurate clocks were rare and the fastest one could travel was on a galloping horse.

The advent of the railway network, with trains running across the country to a fixed schedule, changed this long-established pattern and each railway company operated a standard time across its whole network. Initially the railways with headquarters in Belfast and Cork used the local time of those cities on the lines they operated but from 1862, with a nationwide network in place, all Irish railway schedules were based on Dublin time2. A time signal was typically transmitted daily to all stations connected to the railway companies’ telegraph networks so that clocks could be set accurately to Dublin time. At some stations, Dublin time was displayed on the clock inside the railway station while local time was displayed on the clock outside. A story is told about the professor of ancient history at Trinity College Dublin, John Pentland Mahaffy, who, having missed his train, complained to a railway employee that the clocks outside and inside the station had two different times. The railwayman was unsympathetic, replying that there would be no need for two clocks if they both showed the same time3.

This confusion was ended with another piece of legislation. On 2 August 1880, the Statutes (Definition of Time) Act defined Greenwich Mean Time as the legal time for all of Great Britain and Dublin Mean Time as the legal time for all of Ireland. Dublin Mean Time was regulated by Dunsink Observatory, and was 25 minutes 21 seconds behind Greenwich Mean Time. Galway time was now, legally at least, the same as Dublin time with a corresponding reduction in chronologically-induced confusion amongst drinkers and policemen.

The government had, in 1870, taken over the telegraph system from the private companies who had established it. This now nationalised network of wires provided a means to disseminate a time signal instantly around the country so that clocks could be synchronised with “official” time. Over the following decades, as well as standardising clocks and pub opening times across the country, it also embarked on a programme to create a publicly-owned communications network which would further bind together the United Kingdom.

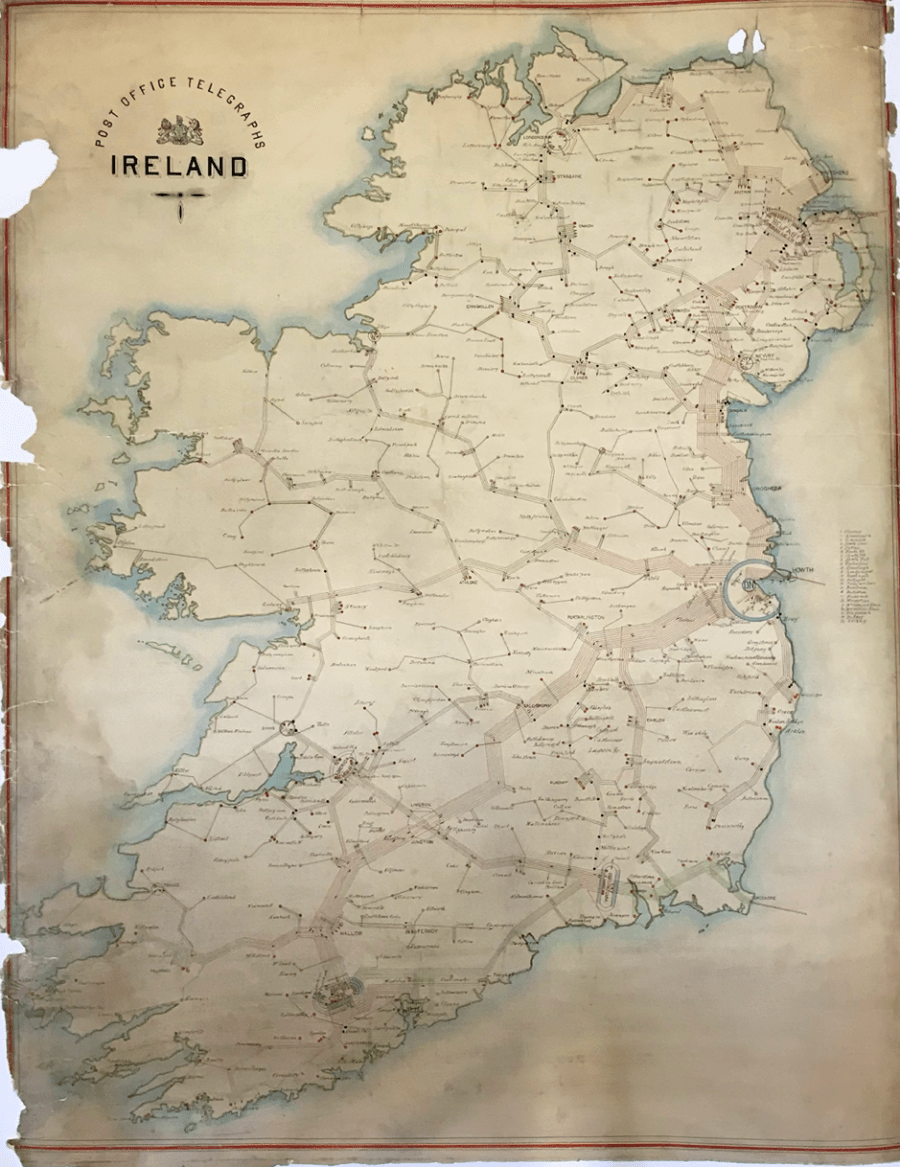

The telegraph network c.18719

The telegraph network c.18719

As early as 1865, Dublin’s General Post Office arranged to receive a time signal at 10am every day from Greenwich4, presumably then offset to Dublin local time. To provide a time signal for ships moored in Dublin Port, a 1.3m bronze time ball was installed in 1865 on top of the Ballast Office beside Dublin’s O’Connell Bridge. This ball was held aloft on a tall pole, and dropped at precisely 1:00pm each afternoon, Dublin Mean Time. Initially it was synchronised with Dunsink Observatory by means a portable clock but in 1874 this was replaced by a leased telegraph line from Dunsink which sent an electrical impulse every second4.

The timeball, with its prominent position in the heart of the capital, became a well-known landmark. In the “Lestrygonians” episode of Ulysses, its position reminds Leopold Bloom of the time “After one. Timeball on the ballast office is down. Dunsink time.5”

The same signal from Dunsink also controlled a clock in the Museum Building in Trinity College4 while a rival system arranged by the Royal Dublin Society supplied a time signal at a cost of £6 12s. (€8.38) per clock per annum. In addition to the Bank of Ireland at College Green, Guinness’s brewery and Arnott’s department store, its customers included the city’s main railway stations4 so that the railways were thus able to relay accurate Dublin time all over Ireland.

There still remained the 25-minute disparity between Ireland and Britain. The pitfalls this could pose for business arrangements were highlighted by the London Times which, with customary chauvinism, told the story of an apocryphal Irishman “…who came on business to Liverpool, and was half-an-hour late for an appointment. He exhibited his watch in evidence of his punctuality, and when it was explained to him that he had local time, and that the sun rose half-an-hour later in Ireland than in England, he bitterly protested against the arrangement as another injustice to his bleeding country.”6

The 25-minute difference was increasingly an anachronism, especially after the Prime Meridian Conference at Washington DC in 1884 when representatives of 25 countries proposed to divide the earth into 24 hours zones one hour apart7. By 1909 the Dublin Chamber of Commerce petitioned other Chambers around the country to support its request to align Ireland with Greenwich Mean Time, noting that “As regards telegrams there is perpetual confusion as to when they were despatched or arrived. The Post Office have found it necessary to take them all by English time, and thus our Post Office clocks have three hands and there are perpetual mistakes.”8

It took the advent of World War I to finally resolve the question of time across the land. The war prompted the government to introduce the concept of summer time and to finally make Greenwich Mean Time the official time for all of the United Kingdom, including Ireland.

By the time it got around to doing so on 1 October 1916, however, the days of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland were numbered.

This is an excerpt from my book project, Connecting a Nation. It tells the story of the pivotal role that telecommunications have played in the development in Ireland from 1852 to the present. Feedback is welcome – especially from publishers !

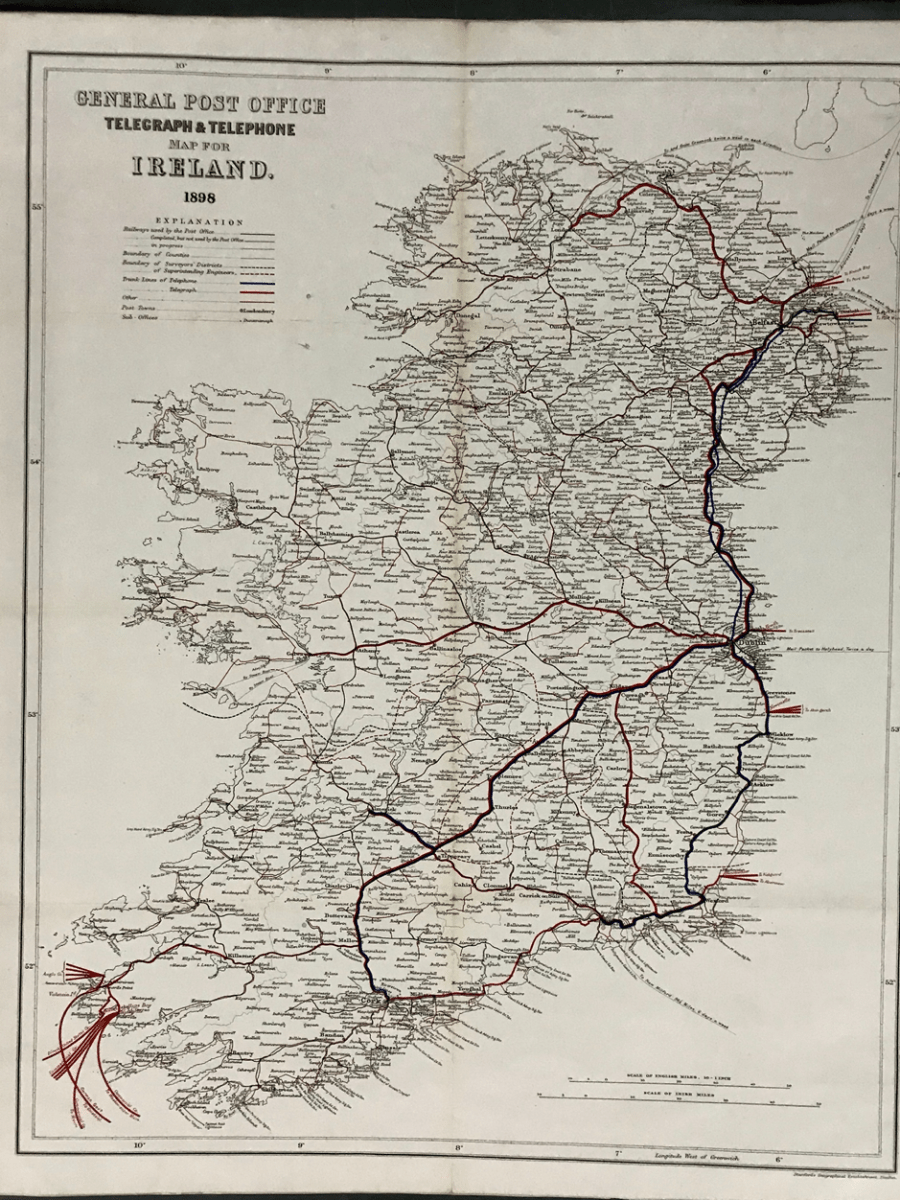

By 1898 the telegraph network, shown in red, covered the entire country from Donegal to Wexford10.

References

- “Dublin Time in Galway”, Roscommon & Leitrim Gazette, 14/07/1877

- McNeill, D. B. . Railway Time in Ireland. Journal of the Irish Railway Record Society, 17(112): 243-245.

- McNally, Frank, “A brief history of (Irish) time”, Irish Times, 31/10/2013

- Wayman, Patrick A. Dunsink Observatory, 1785-1985 : a bicentennial history. 1987, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies and Royal Dublin Society.

- Joyce, James. Ulysses.

- Malone, David Time in the Modern World. 2006.

- Kern, Stephen. The culture of time and space, 1880-1918 : with a new preface. 2003, Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press.

- “A Question of Time”, Waterford Standard, 03/03/1909

- BT Archives, BT-NET1 12/2/1.

- National Archive (UK), Ireland: General Post Office Telegraph & Telephone Map for Ireland: 1898, MFQ 1/1377.

Love it!! Can’t wait to read the whole book 👍👍👌

LikeLike

Deryck – I’m delighted to see all that lovely arcane knowledge of yours properly out in the world.

LikeLike