Lloyd’s of London had a problem with hawks.

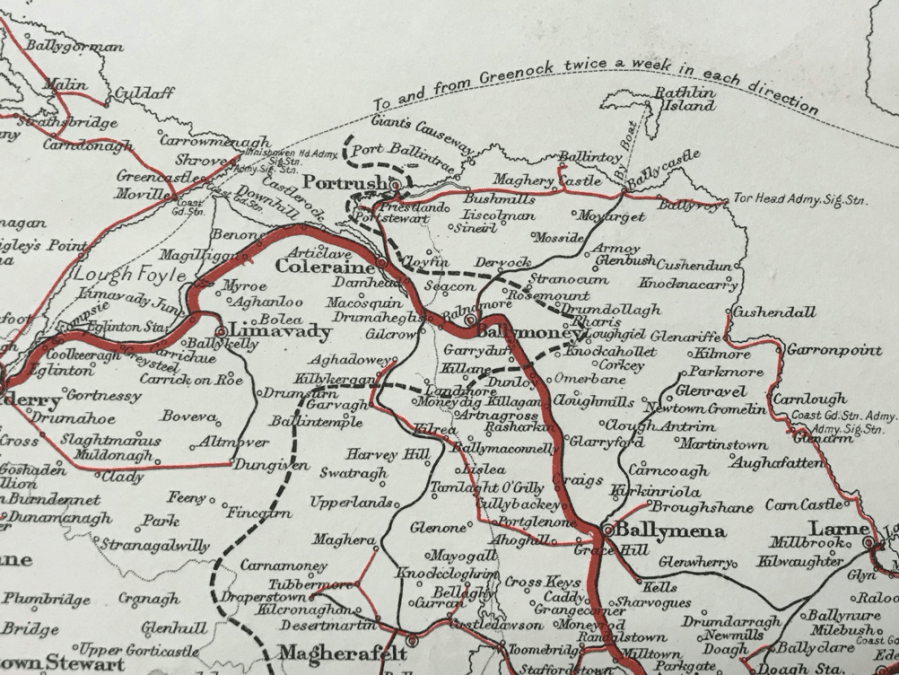

Their station at Torr Head in Co Antrim, part of a network of lookout posts around the coastline, was supposed to inform head office in London by telegraph of shipping movements but the ships were often invisible due to the mist and rain which regularly descended on this isolated headland. The keepers at the East lighthouse on Rathlin island had better visibility of the passing ships but, with no telegraph or telephone connection from the island, it was difficult to forward this valuable information to London. Semaphore signals from the lighthouse to the mainland were also interrupted by poor weather1. Lloyd’s resorted to training a flock of carrier pigeons to fly from Rathlin to Ballycastle Coastguard Station, where the birds would alight on wire netting which rang a bell, thus alerting the coastguard on duty. However, that solution came a cropper when the carrier pigeons were eaten by the hungry hawks that inhabited the island2. Salvation seemed to be on the horizon at last in 1897, when a young Italian man pitched up in London with his mother – and a radically new idea.

The young Italian man was Guglielmo Marconi. Born in Bologna in 1874, he was the son of Enniscorthy-born Annie Jameson whose grandfather John Jameson had founded the famous whiskey distillery in Dublin. The Jameson family had Scottish roots, naming their home in the Donnybrook area of Dublin after the Scottish town of Montrose. (In a neat historical coincidence, Montrose was later to become the home of RTÉ, though sadly there is no evidence that Guglielmo visited the house3.) His Irish mother had a huge influence on his early life, raising him to be fluent in English as well as Italian and constantly nurturing his experiments with technology. When he failed to impress the Italian authorities with his ideas about wireless communication, his mother encouraged him to try his hand in the UK, travelling with him to London in 1896. There, aged 22, he demonstrated his transmitter to several prospective customers in the UK including the Post Office and the defence forces. A veritable 19th century tech entrepreneur, Marconi had filed his first patent, for wireless telegraphy, by the age of 22 and formed his first company when he was 23.

The first technological breakthrough to be promoted by Marconi was the radio transmitter. Marconi’s transmitter was based on spark gap technology that worked by generating radio frequency electromagnetic waves using an intermittent electric discharge — literally a big electric spark controlled by a Morse key. At the receiving end, a device called a coherer was used to detect the distant sparks6. This consisted of a tube or capsule containing two electrodes spaced a small distance apart with metal filings in the space between them. When a radio signal, such as that generated by the spark-gap transmitter, is applied to the device, the resistance of the filings reduces, allowing an electric current to flow through it. This current could be used to produce an audible click and thus the dots and dashes produced by the spark-gap transmitter could be heard across the distance. Spark transmitters and coherers were the technologies behind the first decades of wireless, until both were replaced by devices based on continuous wave technology from 1907 onwards.

While his demonstrations to the Post Office and the defence forces were to reap rewards later on, Marconi’s first real break came when Lloyd’s of London arrived at the door of his London office in 1897. In the 19th century, travel by sea was still a hazardous undertaking. As the world’s leading maritime insurer, Lloyd’s of London compiled details of worldwide shipping movements and casualties, and to this end Lloyd’s utilised lookout stations positioned all around the coasts including many in Ireland. Most of the shipping traffic from the US and Canada en route to ports such as Liverpool, Glasgow and Belfast passed along the north coast of Ireland. Lloyd’s had lookout stations at places along this coastline including Malin Head in Co Donegal and Torr Head in Co Antrim to report this traffic by telegraph back to London. However, with no luck using either pigeons or semaphore to communicate with the mainland, Rathlin island’s East lighthouse was cut off from this network. Lloyd’s, hearing of Marconi’s supposed new invention, arranged a meeting5 in London where the problem at Rathlin island and its hungry hawks was discussed. So, in the early summer of 1898, Marconi ended up in the north-eastern corner of the country of his mother’s birth.

Marconi’s plan was to erect a wireless station at Rathlin East lighthouse which would transmit reports to Ballycastle on the mainland from where they would be relayed to Lloyd’s by telegram. On Rathlin, an aerial of 24m was erected at the east lighthouse. Various sites were tried around Ballycastle for the receiver location with particularly good reception noted when the mast was attached to the spire of the town’s Catholic church7. Apart from the Marconi staff, no-one knew Morse code, so his right-hand-man George Kemp provided some quick lessons to the principal keeper4 at the East lighthouse, Galwayman Michael Donovan, and his sons John and Charles8.

The lessons over, George Kemp returned to the mainland to listen for signals being sent form Rathlin. On Wednesday 6 July 1898 Kemp could make out a few ‘V’s being sent in Morse by Donovan on Rathlin, making the north Antrim coast is the birthplace of radio for commercial use1.

By the end of August the experimental system was working reliably, reporting shipping movements from Rathlin to Lloyd’s via Ballycastle until the experiment was ended in September. Marconi and his growing network of business interests remained involved in Ireland. Following the successful experiments from Rathlin, Lloyd’s installed Marconi-supplied wireless stations at Rosslare, Crookhaven and Malin Head. The latter location is still a marine radio station, playing a vital role in the safety of transatlantic shipping.

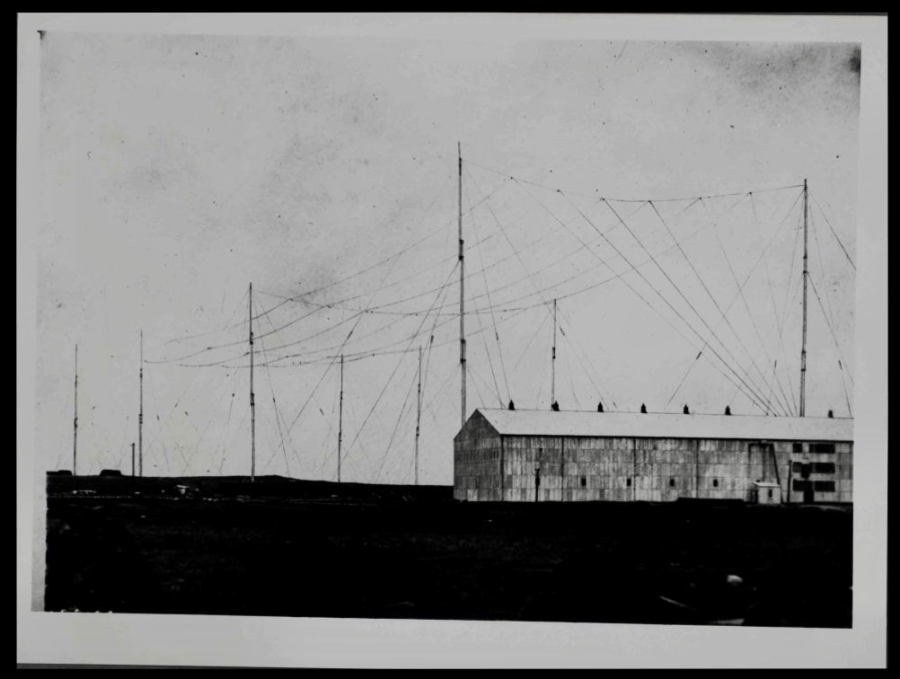

A few years later, Marconi built a massive wireless telegraphic station on a site at Derrygimlagh near Clifden in Co Galway to transmit telegrams across the Atlantic towards its corresponding station in Nova Scotia on Canada’s eastern extremity. The station’s 20,000v spark transmitter, the most powerful in the world5 was powered by a turf-fired 300kw electricity generator.

Within a few years, however, Marconi seemed to lose interest in Ireland. The country became peripheral to Marconi’s now-global business, merely a small market for the company’s equipment.

He became estranged from his Irish-born mother Annie, whose funeral in London in 1920 he did not attend9. His telegraph station at Clifden suffered a triple whammy as the new Irish Free State took shape. With improved radio technology, it was possible to reliably transmit across longer distance and bypass Clifden. But before Marconi had itself ceased operations, the station was taken over by anti-Treaty forces on 24 July 1922 who destroyed the equipment and expelled the staff. The final straw was the attitude of the state’s first Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, J. J. Walsh. He apparently viewed the Marconi company and its Empire-wide radio network as part of the ancien regime and said that he would be happy to see the company leave Ireland for good5. The Clifden facility officially closed in 1925 with its equipment sold for scrap4.

Guglielmo Marconi died on 20 July 1937. As an Italian Senator and confidante of Benito Mussolini, his own state funeral in Rome was orchestrated with military-style pomp and the many wreaths adorning his coffin included one sent by Adolf Hitler10. By the time of his death the radio technology Marconi had championed had become commonplace, not just for broadcasting, but also within the telephone network. However even Marconi himself probably did not foresee that within 90 years most of the world’s inhabitants would have a telephone in their pocket based on the wireless technology he had pioneered.

This is an excerpt from my book project, Connecting a Nation. It tells the story of the pivotal role that telecommunications have played in the development in Ireland from 1852 to the present. Feedback is welcome – especially from publishers !

References

- McCurdy, Augustine. Marconi and Rathlin. Culture Northern Ireland. Available from: http://www.culturenorthernireland.org/article/1316/marconi-and-rathlin [Accessed on: 05/11/2018]

- McGill, Bernie, “Marconi, Rathlin Island and a new way with words”, Irish Times, 10/08/2017

- Warren, Stanley. Montrose House and the Jameson Family in Dublin and Wexford: A Personal Reminiscence. The Past: The Organ of the Uí Cinsealaigh Historical Society, 2007, (28): 87-97.

- Sexton, Michael. Marconi : the Irish connection. 2005, Dublin: Four Courts.

- Raboy, Marc. Marconi : the man who networked the world. 2016, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Homer, Peter. Malin Head Marconi Radio Station. Carndonagh Amateur Radio Club. Available from: http://www.malinhead.net/marconi/Marconi.htm [Accessed on: 28/11/2018]

- Boyd, Hugh Alexander Marconi and Ballycastle. Glens Of Antrim Historical Society. 1968 Available from: http://antrimhistory.net/marconi-and-ballycastle/ [Accessed on: 05/11/2018]

- The National Archives of Ireland. Census of Ireland 1901.

- Masini, G. Marconi. 1998: Marsilio Publishers.

- Robinson, Andrew. Marconi forged today’s interconnected world of communication, New Scientist, 10/08/2016,

- National Archive (UK), Ireland: General Post Office Telegraph & Telephone Map for Ireland: 1898,MFQ 1/1377.

- BT Archives, Clifden Wireless Station condensor house, Galway, TCB 417/E 2104.